I hate when people call The Godfather a mob movie. Goodfellas is a mob movie (albeit one with crazy and compelling characters). I consider The Godfather to be a movie about a family that just happens to be in organized crime. Where a movie like Goodfellas depicts the craziness of that lifestyle, The Godfather treats organized crime no different than any other occupation. Sure, the Corleone Family deals in murder and vice, but Coppola treats their occupation no differently than if they were in sales and commodities. The emphasis is not on the violence, but rather on the characters. As a viewer, I’m more interested in how Michael relates to his family as the outsider or how Sonny and Tom squabble deciding if they should retaliate against a rival family for the attempted assassination of Vito, rather than see Luca Brasi murdered with a garrote.

As a viewer, I appreciate how unique each member of the Corleone Family is and how it drives them. Don Vito is calm and wise, doing everything to advance and protect his family. Sonny is the hothead whose temper and short fuse will eventually be his downfall. The second son Fredo, sometimes a little rascal, is often thought of as weak and lesser. After all, he fails to protect his dad from an assassination attempt while grocery shopping. Tom Hagen, the consigliere, displays more similarities with Vito, like his rational and calm demeanor, despite being the adopted son. Tom even reasons with Sonny that the shooting of their father wasn’t personal. It was strictly business. The youngest child, Connie, because she is a woman, is often excluded from business matters. Given that would have been the norm during the period in which the film is set, Connie has accepted that. Though not blood, Tessio and Clemenza are Vito’s oldest allies and as capos, have great influence in the family. They are trusted unequivocally (which becomes an issue later on).

I deliberately saved discussing the third Corleone child, Michael, for last. Entire essays, maybe even books, could be written about him and his character development. I mentioned this at the start of the post, but I do believe that Michael’s character arc in this film (boosted even further by the second film) is one of the greatest in cinema history. When Michael first appears in the film at Connie’s wedding, he is a war hero. Though many consider Fredo to be the black sheep of the family, you could make a stronger case at this point that Michael is the black sheep. Against the advice of his entire family, Michael enlists in the Marines during World War II. When we first meet him at Connie’s wedding, he tells his date, Kay, violent stories about his family. When she reacts in horror, he reiterates to her “That’s my family, Kay. That’s not me.” For a good chunk of the movie, we believe him.

It’s only after his father is shot that his mindset begins to shift. It’s not to say that Michael didn’t realize the value of family before this, but I believe it starts to hit home when he sees his father lying on a hospital bed, tubes in his nose. Despite staying out of the family business, he springs into action when he sees his father left unguarded and saves him from another attempt on his life. The turning point is when Michael confronts the corrupt Captain McCluskey about the lack of guards at his father’s bedside. McCluskey is so outraged that he assaults Michael, leaving him with a black eye and split lips. In his rage, Michael tells Sonny (who is the acting boss) and Tom that if they can lure McCluskey and Sollazzo to a meeting place, Michael will kill them both. The two laugh it off but eventually relent. Despite working with Clemenza, who plants the gun in the bathroom of the Italian restaurant, it seems Michael is unsure if he’ll go through with it. In a scene of masterclass acting from Pacino, in which we see the gears in Michael’s head turn, he leaps and pulls the trigger on both men. This is Michael’s point of no return.

To avoid the police crackdown and all-out warfare between the five families, Michael is sent to Sicily. Though the length of his stay is not explicitly stated, it is implied that he was hiding under the hand of Don Tommasino (one of Vito’s allies) for at least a year. During his time in Italy, he starts to learn the culture and marries a woman named Apollonia. His time abroad is cut short when Apollonia is killed in a car bomb meant for Michael. Meanwhile, back in New York, Sonny is murdered in a hail of gunfire. Devastated by his son’s murder, Vito regains power and makes a deal with the heads of the five families: he will not oppose the other family’s venture into drugs and will not avenge Sonny’s death in exchange for Michael’s safe return to the U.S.

Michael returns to New York as a changed man. He’s becoming more and more removed from the man he was at the start of the film. He’s killed men, seen attempts on the lives of his family members, and his wife blown up. He knows there’s no going back. He marries Kay, has a couple of children, and officially enters the family business as the second in command. Slowly, as Vito’s health grows weaker, Michael takes control of the family. Before Vito dies, he warns Michael that Don Brazini ordered Sonny’s murder and that at a meeting organized by a traitor within the family, an attempt will be made on Michael’s life.

With Vito gone, Michael tries to consolidate power in New York. In a meeting set up by the traitorous Tessio, Michael orders his men to murder the heads of the five families. This all occurs in a beautiful contradictory sequence that shows Michael renewing his baptismal vows as he stands godfather to Connie and Carlo’s son, while his men commit the murders he ordered. With his power consolidated, his final violent act is to have his brother-in-law Carlo killed for his role in Sonny’s murder. An upset Connie accuses Michael of murdering her husband, which he vehemently dies. Realizing that her husband may be a killer, she asks him about Carlo. Michael denies this and tells Kay not to ask about his business. After much pressing, Michael relents and allows her to ask. Kay asks him point blank if he had anything to do with Carlo’s death. Michael lies to her with ease.

As Kay walks out of Michael’s office reassured, that reassurance disappears when she sees two men kiss his ring. She knows the truth. It’s only appropriate that Coppola closes the film with a shot of Michael closing the door on Kay. So much for, “That’s my family, Kay. That’s not me.” She realizes the man she fell in love with all those years ago is not the same man she is married to now. In just short of three hours, Michael has transformed from a respectable war hero to a detestable crime boss. That’s why, if you look at Pacino’s performance in this film alone, I would say it is one of the greatest character arcs on film. Pair that with his arc in Part II and he’s a character for the ages.

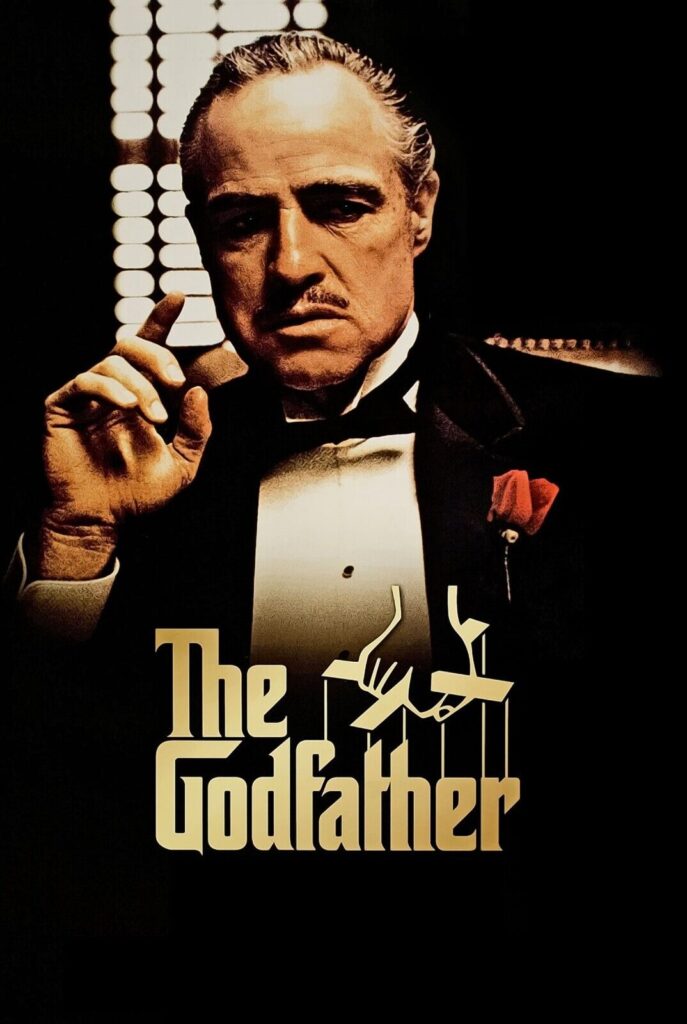

It’s no surprise that the first film was nominated for so many Oscars. I was going over the nominated films of early 1973 and as someone who considers themselves a movie buff, I was surprised to realize that the only Best Picture nominee I had seen that year was The Godfather. I’ve never seen The Emigrants, Sounder, or Deliverance (which I have no desire to see due to its disturbing subject matter). Believe it or not, I’ve never even seen Cabaret. I should add that because of writing this piece, I have added Cabaret to my watch list. Brando’s win for Best Actor and the film’s win for Adapted Screenplay makes sense to me. I can live with the Picture/Director split. It’s a lot more common these days, but back in the 70s, it wasn’t all that common. The split makes sense to me, as both Cabaret and The Godfather scored the most nominations of any film that year (10 each). It makes sense that Fosse won Best Director over Coppola because from what I understand, Cabaret is a “showier” piece.

The category I am most conflicted about is Supporting Actor. I can’t knock Joel Grey’s Oscar-winning performance since I haven’t seen the film, but I heard it’s amazing. I never saw Eddie Albert’s performance in the original The Heartbreak Kid (though I did see Ben Stiller’s abysmal remake). I often find myself wondering if I was an Academy voter during this time, whom in this category I would have voted for. Perhaps Joel Grey was deserving or perhaps the three contenders from The Godfather split the vote. Even though I admitted to not seeing The Heartbreak Kid, Albert still probably was not in contention for my vote. I think Robert Duvall is a great actor and his character is an essential part of the story, but I don’t think his portrayal warranted a nomination. For me, this would come down to Caan vs. Pacino. There was some controversy that Pacino was nominated in the Supporting Category instead of the Lead Category. I can’t say I disagree. He was a second lead and even had more screen time than Brando. The rumor was that Pacino boycotted the Oscar ceremony for this reason. This was recently debunked by Pacino in his memoir, who explained that it was his anxiety that came with his newfound fame that kept him from attending. This is a tough call. If I voted based on the magnitude of the overall performance, Pacino would get my vote. If I voted for the best role that I strictly believed was a supporting performance, Caan would get my vote.

Part II could have easily been a bloated misfire, but somehow, it works. This is due in large part to the compelling characters. Except for Brando and Castellano, the entire cast returned, along with the additions of De Niro, Gazzo, and Lee Strasberg as Hyman Roth. The return of Pacino was in question. He had become a major star since the release of The Godfather and had earned another Oscar nomination for his role in Serpico. Allegedly, Pacino was unhappy with the initial script and initially refused to show up for the first day of filming. It was only after Coppola spent the night rewriting that Pacino agreed to show up to the set. There are a few actors in the film I want to single out, starting with Robert De Niro. De Niro, despite starring in Martin Scorsese’s Mean Streets, was relatively unknown when he was cast as a young Vito Corleone. This was his breakout role.

Vito’s rise to power parallels that of Michael. Vito comes to America as an orphan in the twentieth century and takes refuge in New York City. Initially, he is determined to make an honest living to support his wife and son. Slowly, his view of the neighborhood begins to change. He loses his job to the nephew of the “Black Hand” Don Fannuci and meets Clemenza and Tessio, who introduces him to the world of crime. When Fannuci discovers their activities, he attempts to squeeze them. Vito, who sees how cruel and unfair Fannuci is, decides he needs to take a stand. He first pays the Black Hand considerably less than was demanded. Impressed by his boldness, Fannuci lets this slide. Once he is in the Don’s good graces, he shoots and kills him as the city is distracted by a parade. It’s implied throughout the saga that Vito does whatever he needs to protect his family, including ordering murders, but this is one of only two times we see Vito murder someone himself.

With Fanucci dead, Vito claims his stake in the American dream, becoming the de-facto-Don. Whereas Fanucci used fear and intimidation, Vito used honor, loyalty, and respect. Over time, Vito starts an olive oil import company and amasses more and more power, eventually becoming the Don we recognize from the start of the first film. De Niro is impressive, considering most of his performance is physical and internal. He doesn’t speak often, but when he does, it’s mainly in Italian. De Niro is one of the few actors to win an Oscar for a primarily non-English speaking role. Others include Sophia Loren in Two Women and Roberto Benigni in Life is Beautiful (both Italian), Jean Dujardin in The Artist and Marion Cotillard in La Vie en Rose (both French) and Benicio Del Toro in Traffic (Spanish). De Niro would go on to receive eight more Academy Award nominations (winning for Raging Bull) and cementing his status as one of the greatest actors of all time.

Though not as prominent as De Niro, both Diane Keaton and Talia Shire give strong performances as two of the most important women in Michael’s life. Keaton is phenomenal as Kay. Until the final scene of the first film, Kay is depicted as a woman naive to her husband and his family. By the time the second film starts, she’s been in this life long enough that she knows there is no choice but to keep pushing forward and stay out of her husband’s business. She marches forward until she can’t any longer. She ultimately hits her breaking point when she decides she can no longer bring another one of Michael’s sons into the world and commits the ultimate betrayal. She knows the only way out is for Michael to force her out, but that comes at the cost of seeing her children.

Connie’s arc is vastly different from Kay’s. In the first two films (minus a brief prologue in 1901 Sicily in Part II), we first encounter the modern-day Corleone family at a religious celebration. In the first film, it’s Connie and Carlo’s wedding. In the second, it’s Anthony’s first communion. Between the start of the two films, Connie has changed significantly. She goes from a wide-eyed newlywed to a selfish socialite. She’s been widowed from her first husband and divorced from another. When we first see her in Part II, she is engaged again. Her top priority is to meet with Michael and ask for money for her wedding. Mama Corleone quickly sets her straight, telling her “First you see your kids, then you go see your brother. She’s been an absentee mother, a fact Michael drives home when she tells him that her son was picked up for shoplifting. Disappointed, Michael tells Connie that he will disown her if she goes and marries this man. Still angry and hurt at Michael for killing Carlo, she refuses to call off the marriage and storms off. She then disappears for a large amount of time, returning towards the end of the film. She eventually makes peace with Michael and begs him to forgive Fredo (something we’ll get to momentarily). This is the scene that no doubt secured Shire her Academy Award nomination for Best Supporting Actress. However, if only one actress from the film got a Supporting Actress nomination, I would have preferred Keaton. The scene where she reveals to Michael that she had an abortion should have sealed the deal in my book.

The next performance I want to recognize is that of the late John Cazale. A well-respected theater actor from New York, Cazale made his film debut at age 36 playing Fredo Corleone in The Godfather. Despite no previous film appearances, he had no problem holding his own against the likes of Brando, Duvall, Caan, and Pacino. His role in the first film isn’t huge, but it is important. It’s implied early on that Fredo is the weak Corleone child. The oddball, yet loveable child. This is most apparent when Vito is shot at the outdoor market, all while Fredo fumbles with his guns, letting the shooters escape. When Sonny becomes acting boss, he sends Fredo away to Las Vegas to learn the casino business. As much as he is sent to learn the trade under Moe Green, it is just as much for his safety. The implication, of course, is that Fredo cannot take care of himself. When Vito skips him in favor of installing Michael as the new Don, it creates a rift between the two. The rift expands when Fredo takes sides with Moe Greene on an issue and Michael chastises him, telling him “Never take sides with anyone against the family ever again.” This rift would continue to grow until it reached a tragic breaking point in Part II.

As we begin Part II, Fredo is officially Michael’s underboss, though it seems to be a name-only title with limited power. Fredo does nothing to help his reputation as the black sheep Corleone when he cannot control his drunken, domineering wife on the dance floor at the celebration of Anthony’s First Communion. Fredo apologizes to Michael for being unable to control his wife as one of Michael’s bodyguards leads her away. Michael comforts Fredo, telling him “You’re my brother. You don’t have to apologize for anything.” To the untrained eye, Michael could easily be mistaken for the older brother, the protector. The festivities are cut short that night when there is a failed assassination attempt on Michael. Because it occurred within his family compound, Michael suspects that there is a traitor in the family.

A major plot point in Part II involves Michael entering negotiations with rival mob boss Hyman Roth. After the attempt on Michael’s life, Michael goes into hiding, placing Tom in charge of the family. Additionally, he sends Fredo to Cuba because Roth is interested in investing in Havana under the Batista government. At the end of 1958, Michael and his associates join Roth and his associates in Havana to discuss terms. After seeing a rebel soldier blow himself up, Michael expresses doubts about doing business in Cuba. At a party on New Year’s Eve 1958, Fredo slips up and reveals that he was working with Hyman Roth’s right-hand man Johnny Ola, ultimately implicating him as the traitor within the Corleone Family. Michael is devastated, going as far as giving him the infamous “kiss of death.” Michael, Fredo, Roth, and their associates quickly flee as Batista is overthrown on January 1, 1959, marking the start of the Castro era.

The film doesn’t reveal specifically how Fredo helped Roth and if he knew his intent to assassinate Michael. When Michael confronts him, Fredo swears he did not know about the attempt. He angrily explains to Michael that as the older brother, he resents being passed over to lead the family and that Hyman Roth promised him something “for himself, on his own.” He explodes as he laments to Michael that he can’t stand being considered lesser than. “Poor, stupid Fredo. Let’s send him to do some Mickey Mouse nightclub bullshit,” he rants. He begs for his brother’s forgiveness, but instead, Michael disowns him. He utters the words that hit Fredo like a dagger through his heart, “You’re not my brother. You’re not a friend. You’re nothing to me.”

Never one to forgo revenge, Michael tells family hitman, Al Neri not to harm him while their mother is still alive. Eventually, Mama Corleone passes away. As previously mentioned, Connie begs Michael to forgive Fredo, which he does publicly. Shortly, however, Michael gives Neri the order to kill Fredo, which he does while they are fishing on Lake Tahoe. One of the film’s final scenes is a flashback scene taking place on December 7, 1941, which happens to be both Vito’s birthday and the attack on Pearl Harbor. While waiting for Vito, Michael, Sonny, Fredo, Tom, and Connie sit around the table. Connie and her new beau Carlo go to the kitchen to decorate the cake. Michael mentions that he enlisted in the Marines. Sonny is angered at Michael’s decision to risk his life for his country because “your country’s not blood.” Tom is perplexed. After all, he and Vito worked to get a deferment for Michael because his father had big plans for him. Only Fredo was supportive of his decision. How ironic.

The last performance I will talk about is Al Pacino. I believe that his performance in this film is his magnum opus and I will die on that hill. Michael, in this film, is suave and intelligent, yet cunning and ruthless. He puts on a front as an honorable and philanthropic individual but has ulterior motives. He blackmails a corrupt senator who tries to extort him, has Tom guilt Frankie Pentagali into committing suicide so he cannot testify in the senate against Michael, orders the death of Roth, banishes Kay from his and their children’s lives, and possibly worst of all, orders the murder of his brother. That penultimate flashback scene perfectly contrasts the final scene where Michael sits alone in a mess of his own making. He’s miles and miles away from the young, righteous college student eager to make his way by joining the Marines. He’s a man who has lost his soul. Pacino’s performance is simply impressive. There’s no other word for it.

When it comes to the Oscars, I have mixed feelings. Part of me is surprised that the film was nominated for and won so many awards, but then part of me isn’t. The part of me that was surprised was because the film was a sequel to a Best Picture-winning film, thus, there may have been the mindset that the film didn’t need to win. Also, I was partly surprised because Chinatown seemed to be a major contender. It won quite a few precursor awards including several Golden Globes. On the other hand, I can understand the mentality of rewarding a sequel to The Godfather that manages the rare feat of matching, if not top, the original. Also, maybe the Academy felt the need to award Coppola the Best Director trophy as a way to make up for denying him two years prior. Ironically enough, Coppola was facing off against Fosse again, this time for Lenny, the Lenny Bruce biopic starring Dustin Hoffman. Unlike last time, however, Fosse didn’t have a chance. Roman Polanski (Chinatown) was undoubtedly his main contender. I realize this example is about ten years old now, but I feel like this year was very much The Godfather Part II vs. Chinatown, just like 2015 was a showdown between Birdman and Boyhood.

Aside from Director and Picture, the film’s other wins make sense to me. No complaints there. I mentioned I would have loved to see Keaton get a nomination for Supporting Actress, but I am happy Shire got a nomination too. I’ve mentioned in previous posts about how one of the Academy’s biggest mistakes was awarding Art Carney the Best Actor trophy for Harry and Tonto over Pacino (or even Nicholson), so I won’t go into that. You can read about it here. Supporting Actors is the category I want to pay special attention to. It’s crazy to me that, alongside the first film, this film also received three nominations in the category. Unlike the 1973 Academy Awards, I had seen the other two nominated performances in the category. Jeff Bridges was fine in Thunderbolt and Lightfoot. I thought he was better in his first nominated film The Last Picture Show. As a Nebraska native, I’m glad that Fred Astaire has an Oscar nomination, but for The Towering Inferno? No. Just no. It’s a fun movie and it deserved its win for cinematography, but none of the performances screamed “Oscar!” In theory, he was probably in second place for the award, having won the same category at the Golden Globes (nobody from Part II was nominated).

I think De Niro’s win was great. No objections. Lee Strasberg’s nomination, I understand. I don’t think he was a revelation by any means. He was a famous acting teacher at the Actor’s Studio, having taught stars like James Dean, Jane Fonda, Marilyn Monroe, Dustin Hoffman, and even co-stars Pacino and De Niro (just to name a few). Making his film debut at age 72, I am convinced that the nomination was more of a way to honor his legacy than his actual performance. Like I said, I can live with this nomination. The nomination that baffles me is Gazzo. He’s serviceable as Frank Pentangeli but I don’t think he’s anything special. Interestingly enough, if you look at Gazzo’s IMDb page, the only award that he was ever nominated for was the Academy Award for this film. There’s not a single other nomination or win on his page. What baffles me further is how Gazzo got in but not Cazale. He is heartbreaking when he finally bursts and gives Michael a piece of his mind. Cazale’s legacy is an amazing one. He only appeared in five films before his untimely death by lung cancer at age 42, but each of them was nominated (or won) Best Picture. Those films were The Conversation and Dog Day Afternoon (nominees) and winners (The Godfather, The Godfather Part II, and The Deer Hunter). Despite this, Cazale was never nominated for an Oscar himself. The closest he came was a Golden Globe nomination for Supporting Actor for Dog Day Afternoon. That’s a damn shame if you ask me.

We finally arrive at Part III. I don’t have nearly as much to say about it as I do the first two installments, but I do have some thoughts. First, a little disclaimer. Though it’s been a while, I have seen the theatrical cut of Part III. That being said, the copy I own on Apple is Coppola’s 2020 re-edit, so that’s what I’m basing my thoughts on. The consensus is the re-edit, retitled The Godfather Coda: The Death of Michael Corleone, is a slight improvement over the theatrical release. Notice the word slight. The quality is still lacking compared to the first two films. Some of the stuff with Joey Zaza and Don Altobella doesn’t make a lot of sense to me, but the whole Vatican banking plotline and their shell company confuse me. Is Michael just trying to help out the church to perpetuate the myth that he’s an upright citizen or is it to help earn forgiveness for ordering Fredo’s murder? In my defense, I’m sure if I wanted to figure it out, I could. The fact is I was so underwhelmed by the film, that I didn’t care enough to try to make sense of it all. It sounds lazy, I know.

The two performances I want to talk about are Andy Garcia and Sofia Coppola. Andy Garcia is electric as the loyal and hot-tempered Vincent. If the film was to receive only one acting nomination, I’m glad it was him. Though I can agree that his performance was lacking compared to the first two installments, I thought Pacino had just enough momentum to score a nomination, but I was wrong.

Let’s talk about Sofia Coppola. I won’t sugarcoat it. This is a terrible performance. A performance so bad, that it earned her a Razzie Award. That being said, I don’t think Coppola is the one to blame here. I think in many ways, her father is to blame. Sofia stepped in at the last minute for Winona Ryder, despite having very little acting experience. She had cameos in most of her dad’s films, including Rumblefish and she even played the baby during the baptism scene in the first Godfather. I can understand a father having faith in his daughter and wanting to cast her, but as director, he should have taken that extra time to cast someone with more experience. Someone who has proven acting abilities. I also believe the elder Coppola bears responsibility as a co-writer. Many of the lines written for the character fall flat, but to me, the most cringe element of this performance is how she is romantically enamored with Vincent, her first cousin. That just does not sit right with me.

I do feel bad for Sofia. She was 18 years old with no real acting experience, stepping into this role because her father asked her to. I don’t believe she should have had to constantly be singled out in the criticism of the film during every review. I have to think about the societal changes over the last thirty years and wonder if the film had been released today, would we be as harsh to this 18-year-old girl now as we were then? I’d like to think we would, but I’m not entirely sure. Luckily for us, Sophia bounced back, following in her father’s shoes. She’s had great success directing movies like The Virgin Suicides, and Marie Antoinette, and won the Academy Award for Best Orginal Screenplay for what is undoubtedly her magnum opus, Lost in Translation.

Before I end this post, I have to discuss what could have been: The Godfather Part IV. Before Puzo’s death, he and Coppola discussed a fourth installment with a structure similar to Part II. The film would have had De Niro reprise his role as Vito Corleone in the 1930s as he introduces Sonny into the family business, while also featuring Garcia as Vincent, running the family through a destructive time during the 1980s. Leonardo DiCaprio was being eyed to play a young Sonny, and according to Garcia, the film was close to being made. Unfortunately, Mario Puzo died in 1999 and Coppola did not feel comfortable moving forward without his collaborator. Thus, the story of the Corleone family went out on a whimper.

Despite the underwhelming nature of Part III, I’m thankful that we have the first two installments. For any filmmaker or writer of any medium, these films are a case study of near-perfect character development. I’m not sure how best to wrap up a post about films as iconic as these. I’ll just say, if you haven’t seen these films, just watch them. They may just change your life like they did mine.