As always, potential spoilers ahead.

After a five-year hiatus following the release of Punch-Drunk Love, Anderson was back in top form for what many consider his magnum opus, There Will Be Blood. The film follows Daniel Plainview, a ruthless oilman dedicated to achieving success at any cost during the oil boom of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The film was notable for being Anderson’s first adaptation. Anderson adapted the first two hundred pages of Upton Sinclair’s Oil! As someone known for original epics like Boogie Nights and Magnolia, I think it showed Anderson’s growth as a filmmaker. It showed me that even though he wrote the screenplays solo, he could identify a good story, whether it came from his brain or someone else’s.

Do you remember the story I mentioned in my last post about how Anderson was doing press for Magnolia and was asked which actors he wanted to work with next? If you remember that question, you will remember that his answers were Adam Sandler and Daniel Day-Lewis. Having worked with Sandler on Punch-Drunk Love, Anderson completes his bucket list by casting Day-Lewis as Plainview. And I must say, it is one of the best casting choices in modern history, but we’ll get to that later. Like Robert Smigel, who showed up as Sandler’s brother-in-law in Punch-Drunk, I was surprised to see Saturday Night Live veteran writer James Downey appear as Al Rose, a local realtor. Downey worked on SNL on and off for about thirty seasons. He wrote for the show from seasons two to five, left, returned, and served as head writer from 1985 to 1995, Weekend Update writer from 1995 to 1997, and contributing staff writer from 2000 to 2013. Downey would have been the head writer when Sandler was a writer/performer on the show from 1990 to 1995.

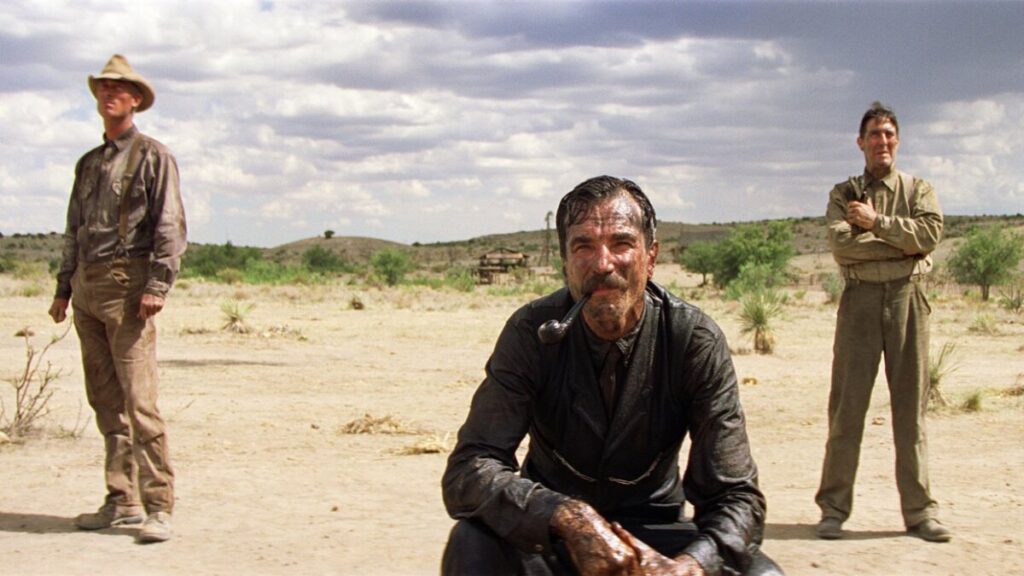

I got that little SNL lore out of the way, so now we can begin. This wasn’t technically my first time watching the movie, but for all intents and purposes, this was. I had seen it many years ago and had forgotten almost everything about the film, except that Day-Lewis gave a towering performance. Film Streams showed a 35mm film print. I love movies, and I’m not picky if it’s shot on film or digital. I know Hollywood films are being shot more and more on digital because it is cheaper and allows for more takes without running out of film. However, I know some film purists like Christopher Nolan and Quentin Tarantino say that digital is not cinema. That’s a little extreme if you ask me, but everyone is entitled to their opinions. From the film’s start, I knew this would be a unique experience. There is no dialogue for the film’s first few minutes, and the sound is minimal. I could hear the film passing through the projector above me. Then, there was the style. The film had a few scratches and imperfections that (aside from being in color) seem reminiscent of the film stock available when the film is set. I don’t remember if that was something I caught when I streamed the film or if it was more apparent because I was watching a film print. Either way, I thought it was a unique approach.

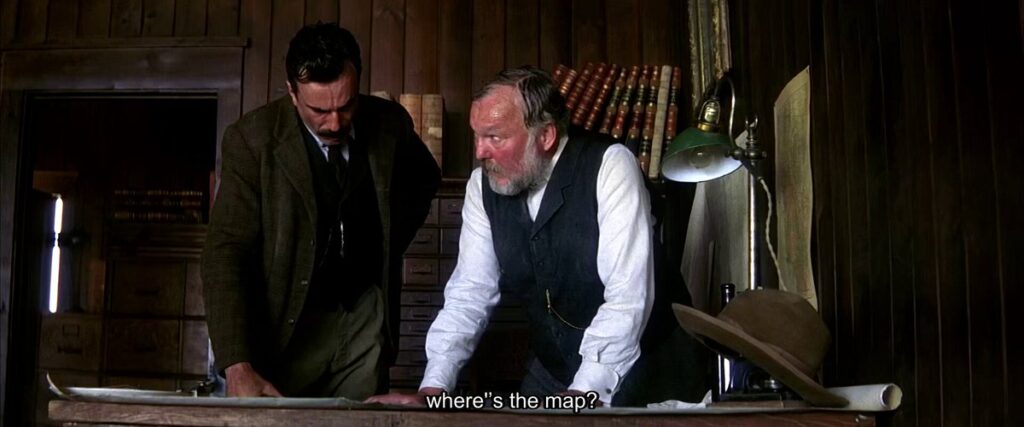

I try not to go too in-depth with my observations here, but the biggest takeaway was the themes of greed, capitalism, and religion at the turn of the twentieth century. Daniel represents the crossover between greed and capitalism. He tells his “brother,” Henry, “I have a competition in me. I want nobody else to succeed.” Throughout the film, he appears as a caring father to his “son” and partner, H.W. Plainview. I use quotations around “son” because H.W. is not his biological son. He is the son of a fellow oilman. When he dies in an accident, he adopts H.W. The audience thinks he loves H.W., and why wouldn’t he? He shows the boy the ropes of the oil business and feels a deep sadness after H.W. is deafened by an explosion on one of the oil derricks. It even appears that Daniel is saddened by his decision to send H.W. away to a school for the deaf.

Eventually, father and son are reunited, and we think their issues have been resolved. Things were going well until 1927. H.W., now an adult, returns to see his father. Daniel lives alone in a mansion and has become a lonely alcoholic. H.W., recently married to Mary Sunday, asks his father to dissolve his partnership so he can move to Mexico with his wife and start his own company. This is where the relationship fractures. A drunk Daniel mocks H.W. for being deaf and says that he cannot dissolve their partnership, as that would make them competitors. H.W. assures him this isn’t true, but just denying him the dissolution isn’t enough. Daniel denies him as his son. While H.W. initially thinks Daniel is extreme by saying he is not his son, H.W. learns the truth about his parentage. Daniel calls him an “orphan,” or worse, repeatedly referring to him as a “bastard in a basket.” The final straw comes when Daniel claims he only adopted H.W. to appear to have a family business, making it easier to convince people to drill on their land. Realizing he has been a pawn in Daniel’s game all of his life, he finally leaves. Whether Daniel had feelings at all for H.W. is left for the viewer to decide. I think saying what he said was a coping mechanism for losing someone close, but others may believe that Daniel was telling the stone-cold truth.

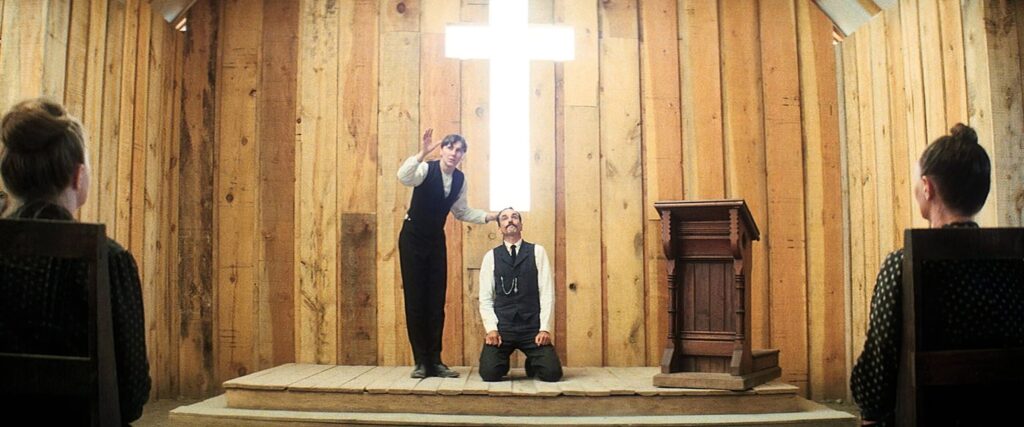

If Daniel is the crossover between greed and capitalism, then Eli Sunday (played excellently by Paul Dano) is the crossover between greed and religion. Though Eli claims to be a man of God, he does many questionable things. He negotiates on behalf of his father, the right for Daniel to drill for oil on the family ranch. He tries to strong-arm Daniel for the money he thinks he is owed and then some. Other questionable decisions he made were telling Daniel that the explosion on the Derrick could have been avoided if he had been allowed to bless the rig before the start of drilling. Instead, Daniel snubs him, and Eli watches the drill burn on the night of the explosion. In a pivotal scene, Daniel reluctantly agrees to get baptised to get the rights to drill on a resident’s land, but in the process, Eli humiliates him, forcing him to yell to God that he is a sinner and that he’s abandoned his child. Eli, under the guise of doing God’s work, clearly enjoys tormenting Daniel. Shortly after the baptism and the assembly of a pipeline, Eli becomes a missionary.

Like with H.W., things come to a head in Daniel’s mansion in 1927. Eli visits Daniel, who is passed out on the floor of his in-home bowling alley. Eli is now a radio preacher who has fallen on hard times amid the economic recession. Eli tells Daniel of a property ripe for drilling and asks for a hefty sum. Daniel agrees, on the condition that Eli renounce God and claim he is a false prophet. Eli initially refuses, but gives in. In the ultimate act of revenge, Daniel reveals that the property has already been tapped. When Eli says there aren’t any drills on the land, Daniel tells him that he could pull in the oil from a neighboring property. The shock in his eyes is priceless as he realizes that he not only has renounced his faith but has been duped by Daniel. Daniel then berates him and explains how he sucked up the oil by using the famous line, “I drink your milkshake.” In another biblical reference, Daniel tells Eli how his twin brother, Paul, visited him all those years ago and gave him the tip on his family’s ranch. How he was paid ten thousand dollars, and Paul is the rich brother, something Eli doesn’t want to hear. Eventually, in a fit of rage, Daniel chases Eli around the bowling alley and bludgeons him to death. In the final scene, Daniel’s servant looks at Daniel, sitting next to Eli’s body, and he utters the perfect final words, “I’m finished.”

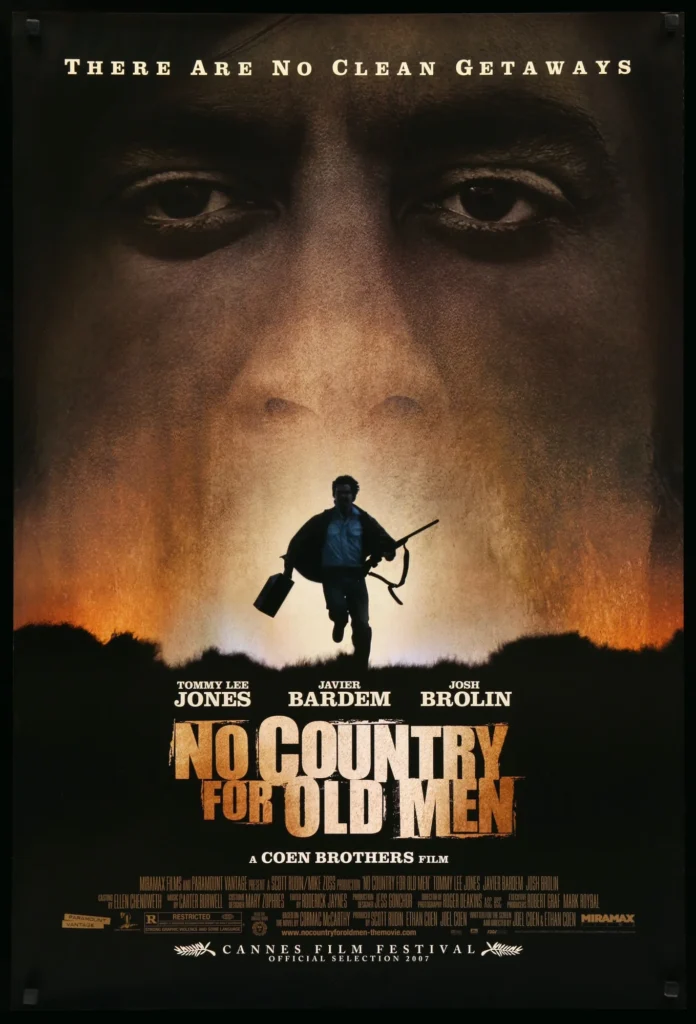

Funding the film took two years, because no studio thought it had the scope of a large cinema. It would take a joint partnership between Paramount Vantage and Miramax before funding could be secured. Luckily, the film was a commercial and critical success. It grossed $76.2 million on a budget of $25 million. It was nominated for eight Academy Awards, earning Anderson his first for Best Director, and making it Anderson’s first film to be nominated for Best Picture. This was a notoriously close Oscar race. No disrespect to fellow nominees Atonement, Michael Clayton, and Juno, but Best Picture was a two-man race between this film and No Country for Old Men. Coincidentally, both films were shot roughly in the same area during the same time. Notably, while rehearsing the rig’s explosion, black fumes made their way over to the set of No Country, causing production to be temporarily halted. The race’s closeness reminded me of Birdman vs. Boyhood in 2015 and, more recently, Anora vs. The Brutalist.

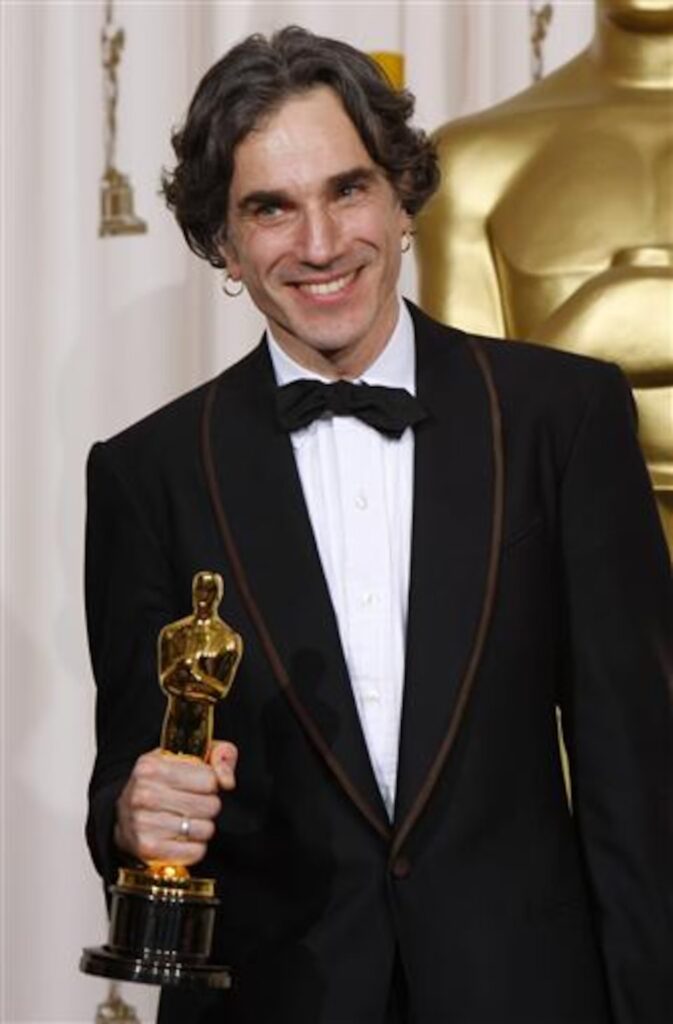

Ultimately, No Country won four Oscars: Best Supporting Actor for Javier Bardem and Best Picture, Director, and Adapted Screenplay for Joel and Ethan Coen. This film didn’t walk away empty-handed. It took home two Academy Awards: Best Actor in a Leading Role for Day-Lewis and Best Cinematography for Robert Elswit. In retrospect, I think the right choice was made. Both films would have been excellent winners, but No Country was the more palatable, even though it’s still relatively unconventional. I think the two awards this film took home were more than justified. Initially, before I saw the movie in theaters, I had a hard time with the cinematography. It had beautiful cinematography, no doubt, but for Elswit to win over veteran Roger Deakins, who had to win an Oscar and was nominated twice that night. The first is for No Country, and the second is for the gorgeous slog, The Assassination of Jesse James, by the Coward Robert Ford. Having seen the film on the big screen in 35 mm film, I have a new appreciation for the cinematography and can rest easy knowing that Deakins would later win for Blade Runner 2049 and 1917. I’m unsure I can say anything about Day-Lewis that hasn’t already been said. He’s arguably one of the best actors of all time, with a resume of memorable titles, and the only actor to win three Academy Awards for Best Actor in a Leading Role. He’s excellent in My Left Foot and Lincoln, but it’s this film that he will be remembered by. It’s no coincidence that this win is often ranked number one if you read lists of the best Oscar-winning performances of the 21st century.

Rediscovering There Will Be Blood excites me for my re-watch of The Master. I remember admiring the performances of Joaquin Phoenix and Philip Seymour Hoffman, but the film was a bit of a bore. I hope to report back with a new mindset. Until then, thanks for reading.

Bonus: The film also inspired this gem from SNL.