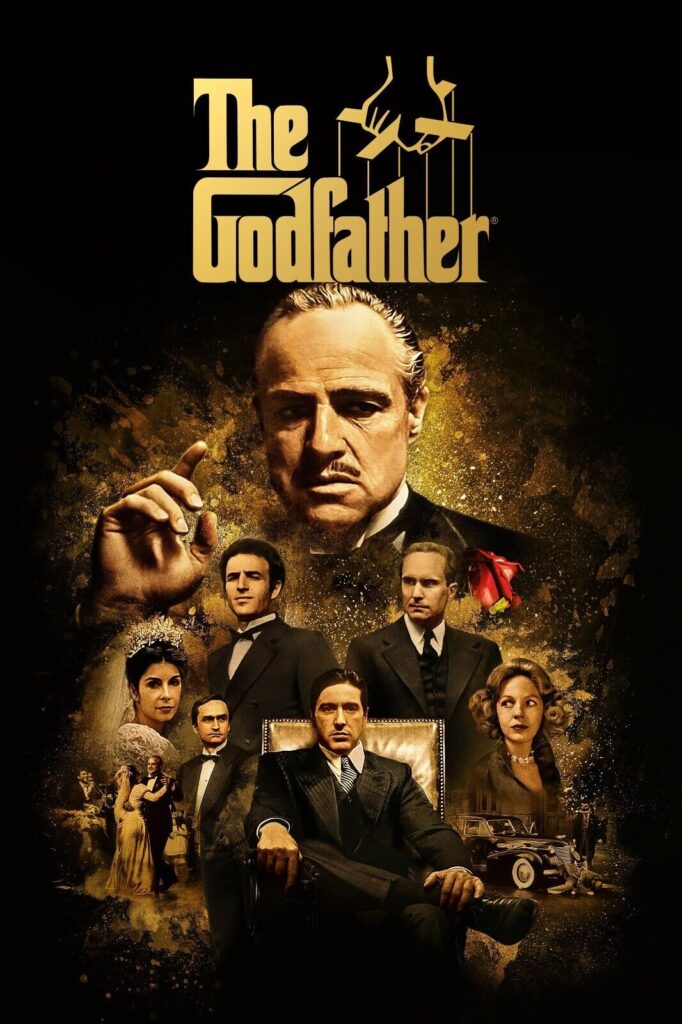

When I started this blog, I knew it would be inevitable that I would write about Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather and its sequels. This last month or so was very Godfather-centric to me. It started at the end of October when I started listening to Al Pacino’s new memoir Sonny Boy. In the book, Pacino talks about his entire life and career, paying special attention to the making of The Godfather and The Godfather Part II. Additionally, in late November my local Alamo Drafthouse was showing movies released in 1974 and I had the luxury of seeing Part II on the big screen. At almost three and a half hours long, it was a test of my ability to sit still, but it was worth it. To this day, it remains the only movie I’ve ever seen at a theater in my lifetime with an intermission. I saw this movie on a Friday night and that Saturday I was compelled to watch Part III.

I’ve said this before, but this isn’t some film school essay. If it were, I don’t think I could say anything new. These films have been analyzed to death. As a film lover, part of me wishes I didn’t like these movies. It’s a cliche to say that the first two films in the trilogy are two of the greatest films ever made. I wish I could disagree and go against the grain, but I simply can’t. Those two films have some of the most compelling characters ever committed to film. I’ll go more in-depth on this later, but I believe that Michael Corleone’s character arc over the first two films (or even just the first film) is one of the greatest in cinema history.

This should go without saying, but since two-thirds of this trilogy is now over fifty years old: spoiler alert. Now, let’s get into it.

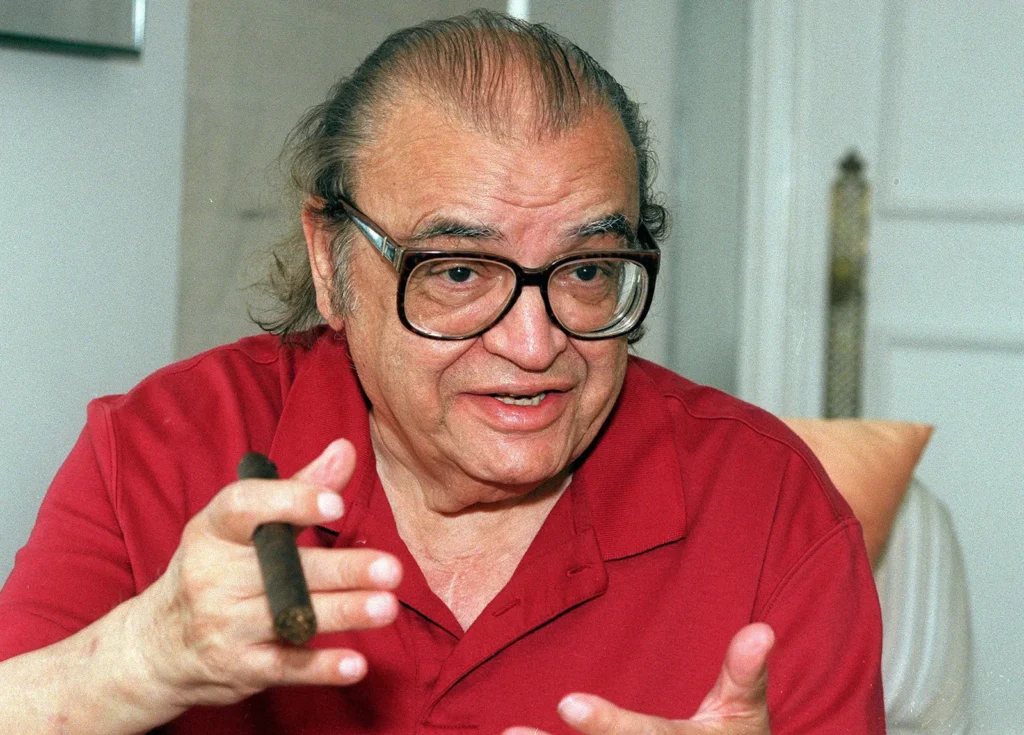

A lot has come to light about the production of the first Godfather film over the last 50-plus years. I won’t bore you with the details, but I will give you the Cliffnotes. Mario Puzo’s original novel, The Godfather, was published in 1969 and was on the New York Times Best Seller list for over a year. 67 weeks, to be exact. Because of the time I was born, it’s hard for me to think of a comparable title. Maybe the Harry Potter or Fifty Shades of Grey books? I recognize those are vastly different, but those are two of the most popular books of my lifetime. If this was any indication of future success, Paramount Pictures purchased the rights to the novel before it was even published. Robert Evans paid Puzo $12,500 to write the script (with an additional $80,000 if the film went into production) and announced a Christmas 1971 release date.

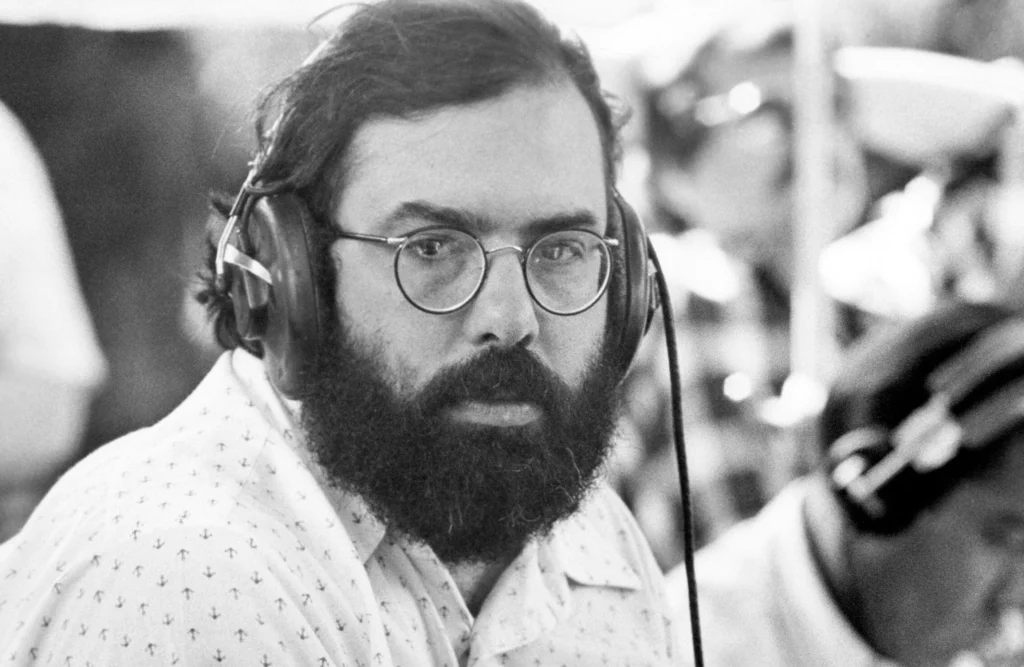

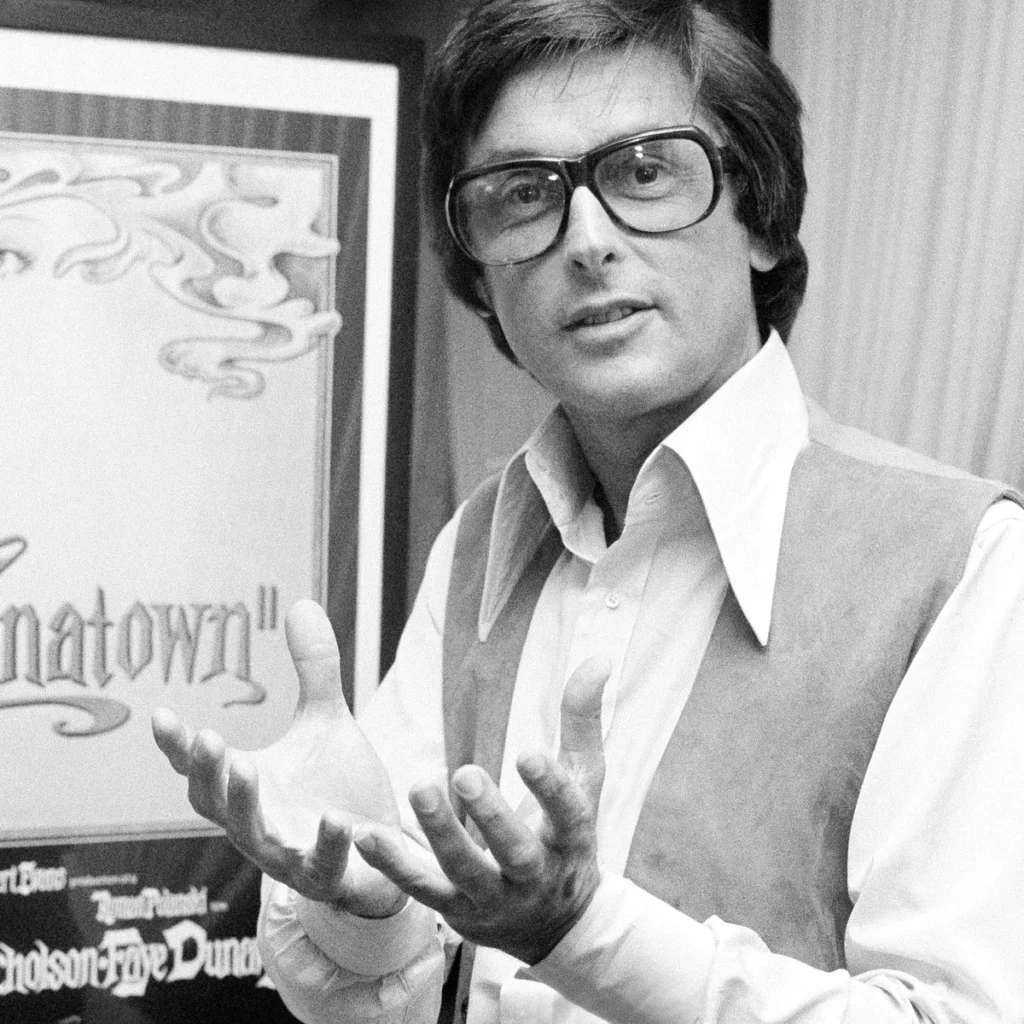

Albert S. Ruddy was assigned to the project as producer and the studio wanted a director of Italian descent. The studio offered the project to Francis Ford Coppola, who they knew would work for cheap after a series of box office bombs. Needing the money, Coppola reluctantly signed on. Before production even began, the film was embroiled in controversy. Many felt the novel depicted anti-Italian sentiments. Joe Colombo, of the Colombo crime family, was one of the most vocal voices against the film. Ruddy eventually met with Colombo and his Italian-American Civil Rights League to get approval on the script. From what I understand, only two uses of the phrase “mafia” and “La Cosa Nostra” were omitted from the final script. Never one to miss an opportunity to cash in, Paramount Plus premiered the series The Offer in 2022 (in time for the film’s fiftieth anniversary), which depicts this and the entire making of The Godfather.

With that out of the way, the rest of the production was smooth sailing.

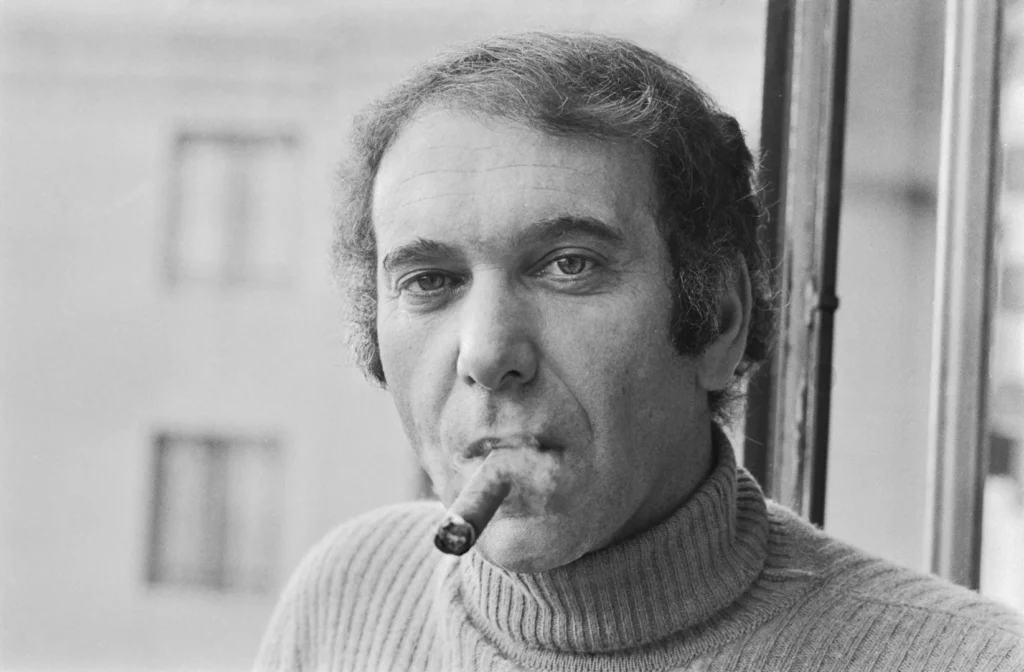

Production was notoriously difficult. From the very start, Coppola and the studio differed in many ways. The studio wanted the film to be set in the modern day to save money. Coppola wanted the film to be a period piece like the novel. The studio wanted an established star for the role of Michael. Someone like Robert Redford or Ryan O’Neal. Coppola wanted a relatively unknown young actor named Al Pacino. For the part of Don Vito Corleone, Coppola only had one actor in mind: Marlon Brando. The studio head was adamant that Brando would never appear in a Paramount picture. Even though he was one of the greatest actors of his generation, Brando developed a reputation for being difficult. Undeterred, Coppola arranged a screen test (under the guise of a “makeup test”) to get Brando on tape. Once the camera rolled, Brando transformed into the Don, slicking back his hair and sticking cotton balls in his mouth to give what Coppola referred to as the “bulldog” look.

Impressed by what they saw, the executives reluctantly approved to cast Brando on the conditions that he worked for cheap and put up a bond to ensure that he would not delay production. With his two leads cast, Coppola got to work casting the supporting parts. He got his choices in Robert Duvall as Tom Hagen, James Caan as Sonny, and Richard Castellano as Clemenza. He rounded out his supporting cast with John Cazale as the second oldest Corleone child, Fredo, Diane Keaton as Michael’s girlfriend turned wife, Kay Adams, and his sister, Talia Shire, as the youngest Corleone child, Connie.

Filming began with the giant wedding sequence. After two weeks of filming, Paramount executives were unimpressed with Pacino’s performance and wanted to replace him. They also had doubts about Coppola, as a couple of crew members began reporting his “incompetence” to the studio. To combat this, Coppola moved up to the pivotal scene in the Italian restaurant where Michael shoots McCluskey and Sollozzo. The combination of violence (some execs thought the film was too dull), paired with Pacino’s internalized performance, impressed the studio brass. Pacino’s job was safe and Evans permitted Coppola to fire the “traitors” within his ranks.

Enlisting an elite crew including cinematographer Gordon Willis, sound designer Walter Murch, and composers Nina Rota and Carmine Coppola (Francis’ father), Coppola worked hard to complete the film in time for its new release date. Released in March 1972, the film was a massive success, becoming the highest-grossing film of the year. As a result of the film, Coppola and Brando found their careers revitalized, Caan and Duvall experienced a new level of fame, and Pacino’s star power shot into the stratosphere. When the Academy Award nominations were announced in early 1973, the film scored 10 nods.

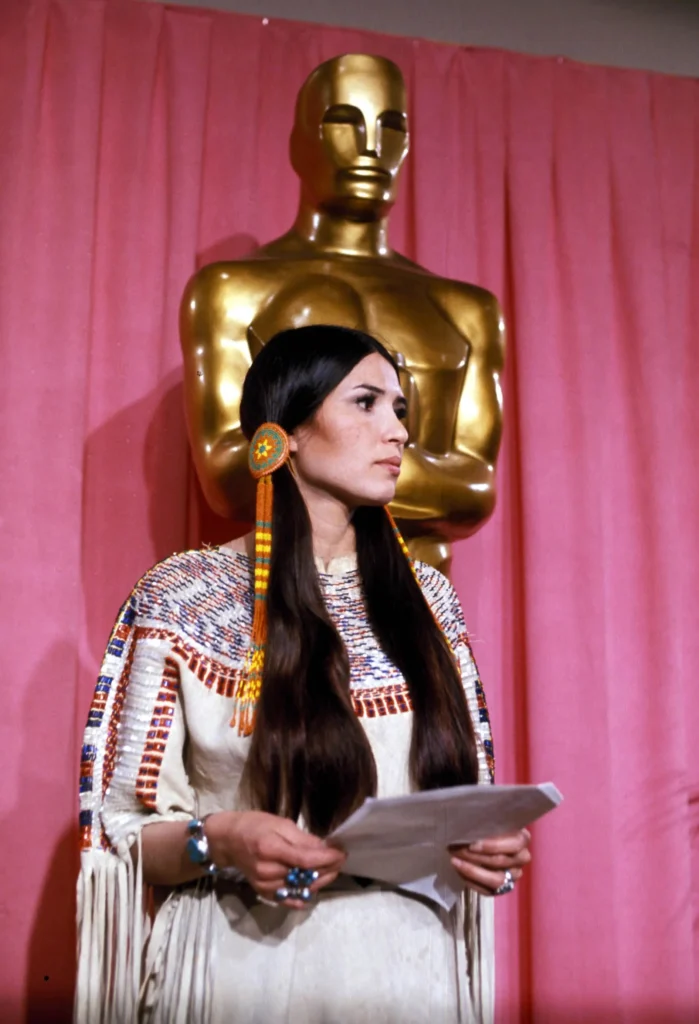

Three of the nominations alone were in the Best Supporting Actor category. Pacino, Caan, and Duvall all received a nomination. The film’s biggest competition at the ceremony was Cabaret. Ultimately, Bob Fosse won the Oscar for Best Director, while the film took home Best Picture. The film also was awarded Best Adapted Screenplay (for Coppola and Puzo) and Brando as Best Actor. Brando notably refused the award, sending up Native American Rights Activist Sacheen Littlefeather to accept on his behalf in protest of the way Native Americans were being depicted in the film. This, of course, caused major backlash.

With a blockbuster as hot as The Godfather, a sequel would surely come next, right? The studio certainly thought so. They hired Puzo to begin a draft in late 1971 before the first film hit theaters. Despite the success, Coppola didn’t think a sequel was necessary. He thought it would tarnish the original. However, the more he thought about the Corleone family and the challenge of making a sequel to such a beloved film, Coppola became invigorated by the idea. His driving force in making the sequel was because he wanted to write a film about a father and son at the same age. He didn’t want to make The Godfather I all over again and the parallel timelines in Part II gave him what he was looking for. The film follows Michael Corleone as he leads his family through many trials and tribulations while paralleling his decline with the rise of his father (Robert De Niro) in 1920s New York.

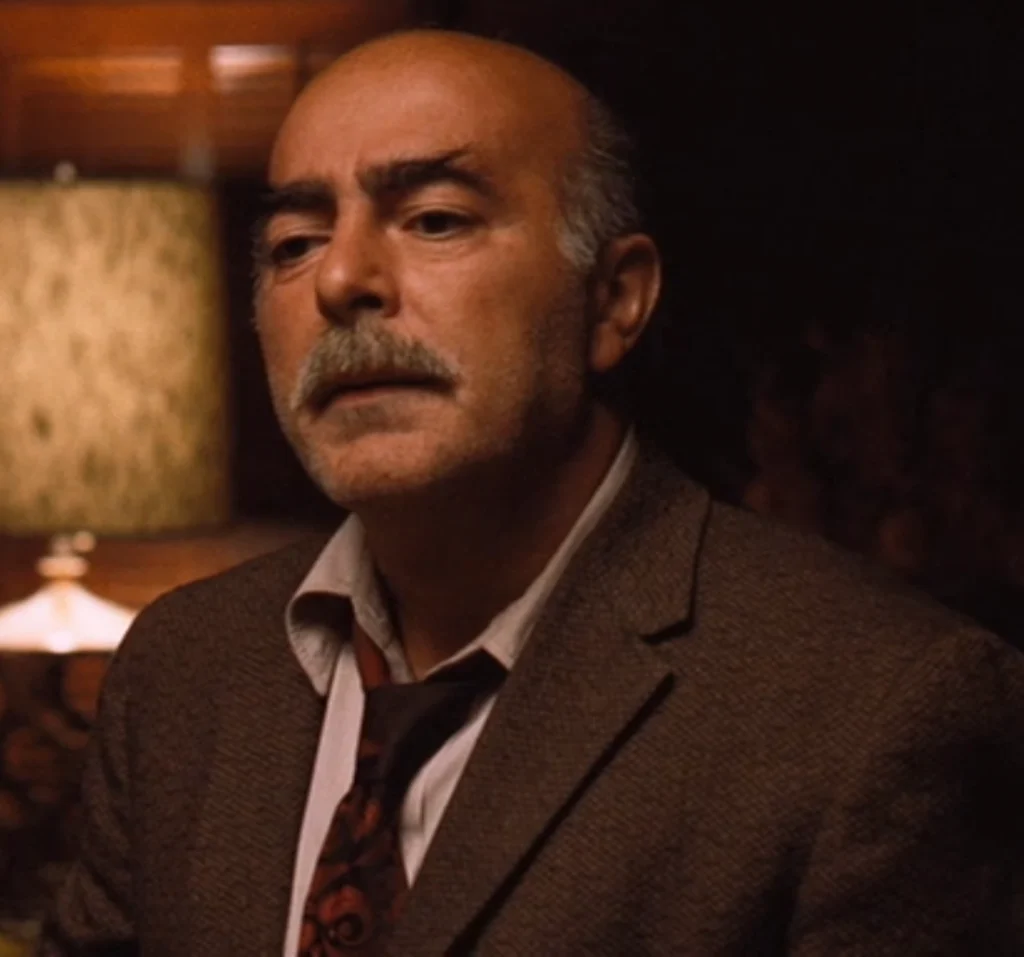

Despite agreeing to rework the script with Puzo, Coppola turned down directing the picture, citing the tumultuous production of the original. He wanted a young up-and-comer named Martin Scorsese, fresh off the film Mean Streets to direct. Paramount balked at the idea and made Coppola an offer he couldn’t refuse. They fired Ruddy (who went on to produce The Longest Yard) and offered Coppola the position of producer himself (along with a nice raise). This resulted in a smoother shoot. Additionally, the majority of the cast returned for the sequel. The notable exception was Richard Castellano as Clemenza. Rumor has it that Clemenza wanted more money and to write his dialogue. His character was later replaced with Frank Pentangeli (played by Michael V. Gazzo). Brando was slated to make an appearance in the flashback scene, but he never showed.

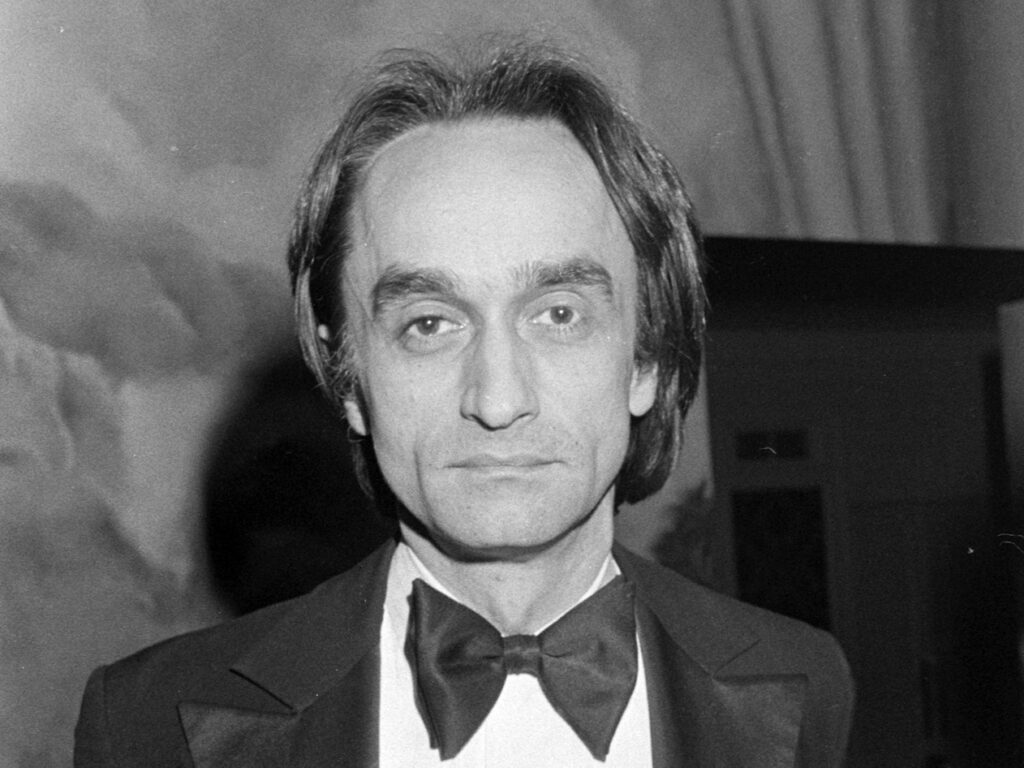

Upon release, the film received divisive reviews. Some deemed it superior to the first and others deemed it to be a mess. Over the years, the film’s status has grown considerably. As of this writing, it is the fourth highest-ranked film by users on IMDb (after The Shawshank Redemption, The Godfather, and The Dark Knight). Despite the varying responses, the film did well on Oscar nominations morning, scoring 11 nominations. Amazingly, like its predecessor, the film received three nominations in the Supporting Actor category (for De Niro, Lee Strasberg, and Michael V. Gazzo). The film managed to double the wins of its predecessor, taking home trophies for Best Picture, Best Director, Supporting Actor, Best Adapted Screenplay, Best Score, and Best Art Direction. With its win, this film became the first sequel to have won Best Picture along with the original, and it would remain only one of two sequels to win (the other being The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King).

Lightning rarely strikes twice, but in Coppola’s case, it did. Would he be able to capture that lightning for a third time? The answer, according to many fans, is an astounding no. Coppola never intended to make The Godfather Part III. The trailers for the second installment bill it as “the final chapter in the Corleone saga.” Paramount, however, had different plans. They forged ahead, developing a sequel without Coppola. Many different scripts were commissioned (you can even find some online) including one based on an outline by then Paramount President Michael Eisner and Puzo himself. The screenplay based on the combined treatments followed Michael’s son Anthony as he teamed up with the CIA to assassinate a dictator and lead the Corleone family. John Travolta and Eric Roberts were even attached to play Anthony at one point. Development stalled in 1985 because the cast of the original films wanted more money than Paramount was willing to part with.

Development officially began again in 1988 when Coppola and Puzo signed on to write the script, which they delivered in May 1989. Like the first film, Coppola only took it on because he was broke. Due to the costly misfires of The Cotton Club and One From the Heart, Coppola needed the money. He signed a deal for $6 million and a percentage of the profit to return as writer/director/producer. Al Pacino, Talia Shire, and Diane Keaton signed on to return soon after. Joining the veteran cast members were the likes of Joe Mantegna, Eli Wallach, and Bridget Fonda. Perhaps the biggest blow was Robert Duvall’s refusal to return. Allegedly, Duvall was unhappy with the pay disparity between him and Pacino. Pacino reportedly received $6 million and Duvall was offered $1 million. He understood Pacino was the star, but he had issues with him being offered six times less than his co-star. The role meant for Tom Hagen was subsequently reduced and merged into the character of B.J. Harrison (George Hamilton).

The two most notable additions to the cast were those of Sofia Coppola and Andy Garcia. Playing Vincent, the illegitimate son of Sonny Corleone, Garcia brought charisma and energy to the screen. Sofia Coppola, on the other hand, did not. Francis Ford Coppola caught a lot of heat for casting his daughter as Mary Corleone, Michael’s daughter. Many notable actors were considered for the role including Madonna (who was deemed too old) and Rebecca Schafer (who was murdered before she could audition). Two other actresses were cast before Sofia Coppola. Julia Roberts held the role briefly before dropping out. Winona Ryder was then cast. She made it to the film site in Rome before dropping out. The official reason given for her departure was “exhaustion” and scheduling conflicts with the film Mermaids. Thus, the role went to the young Coppola. More on her later.

When the film was released in December 1990, it received mixed reviews. Most critics gave it positive notices but noted that it lacked the quality of the first two films. Sofia Coppola bore the brunt of the criticism, as her portrayal of Mary Corleone was widely panned. Despite the mixed reception, the film was nominated for seven Academy Awards including Best Picture and Best Director. Both of those awards were lost to Dances with Wolves. With his Best Supporting Actor nomination, Garcia was the only member of the cast nominated for an award. He would lose the award to Joe Pesci in Goodfellas. This marks two interesting firsts for the franchise: the first Cinematography nomination for Gordon Willis and the first film where Pacino did not receive a nomination.

Those were the Cliffnotes of the trilogy. Nothing you can’t read on Wikipedia. I know what you’re thinking, “Nick, what are your thoughts?” Well, reader, I’m glad you asked. Let’s dive in. I said this up front and I’ll say it again. I wish I didn’t like these movies. It seems to be a cliche to say The Godfather is one of your favorite movies, but damn it if they aren’t masterpieces in my book. We’ll take it one film at a time and start with the first movie. Continue reading for more.